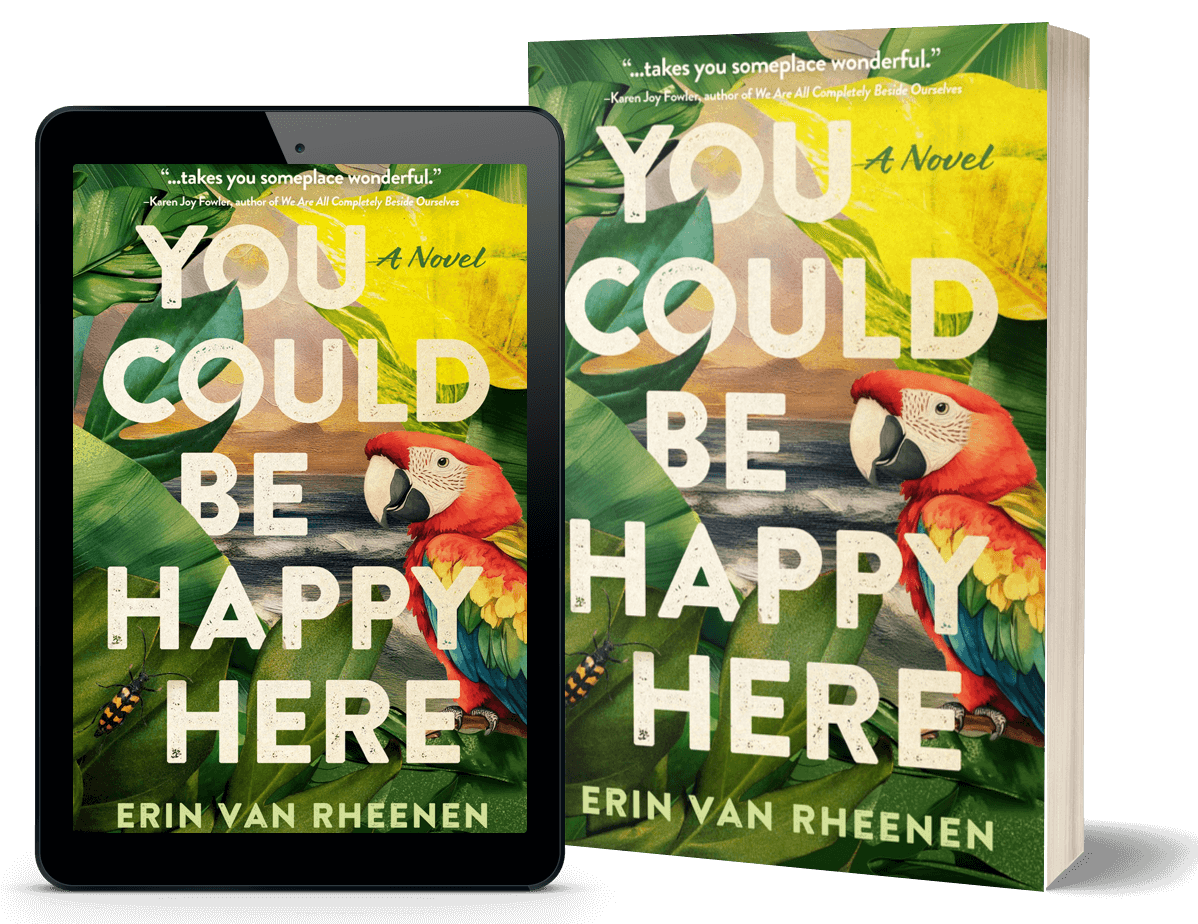

You Could Be Happy Here

Shortly after the untimely death of her mother, Lucy makes a series of discoveries that shatter her idea of who she is and where she belongs. Do her own grief and outrage give her the right to claim her Costa Rican inheritance? Could she be happy there? A gripping novel about how far we’ll go to find our true home.

“Van Rheenen's debut novel ... never goes where you think it's going, but always takes you someplace wonderful.”

—Karen Joy Fowler, author of We Are All Completely Beside Ourselves and Booth

“A brilliant debut and a beautiful tale of personal discovery...

This book may change forever how you think about family and belonging.”

This book may change forever how you think about family and belonging.”

—Pat Murphy, Nebula Award winning author of The Adventures of Mary Darling

Populated by a cast of colorful characters, and buoyed by the customs and culture of Costa Rica, You Could Be Happy Here is a wonderfully insightful story of one woman's journey of discovery.

—Gail Tsukiyama, national best-selling author of The Samurai’s Garden, The Color of Air, and The Brightest Star

A young woman, a tropical paradise, and a past not quite become history—Erin Van Rheenen's new novel is a pleasure to read, full of satisfying complexities.

–Mary Ellen Hannibal, award-winning science writer and author of Citizen Scientist and Spine of the Continent

I found myself rooting for Lucy every step of the way.

—Julia Scheeres, NYT bestselling author of Jesus Land

Beautifully written and soul-searching.

–Sharman Apt Russel, author of What Walks This Way: Discovering the Wildlife Around Us Through Their Tracks and Signs

"I was blown away by the beauty of the prose, as well as the wonder and pathos of the story.”

Nikki Nash, author of Collateral Stardust

This novel bridges the geographic, emotional and cultural gaps the complex characters encounter as they strive to find themselves....

–Polly Dugan, author of The House of Cavanaugh and The Sweetheart Deal

“I actually found myself dreaming about the characters a few times.

They really came alive for me.”

They really came alive for me.”

—David Martin, Ship Captain and long-time resident of Costa Rica

What To Read Where

Subscribe to my Substack newsletter for place-based reading recommendations!